How to Write a Research Proposal ? Achieve Better Curiosity by Proposing Your Willingness to Find Why !!

Your research proposal is a key part of your application. It tells us about the question you want to answer through your research. It is a chance for you to show your knowledge of the subject area and tell us about the methods you want to use.

In your proposal, please tell us if you have an interest in the work of a specific academic. You can get in touch with this academic to discuss your proposal. You can also speak to one of our Research Leads.

When you write your proposal you need to:

- Highlight how it is original or significant

- Explain how it will develop or challenge current knowledge of your subject

- Identify the importance of your research

- Show why you are the right person to do this research

you should endeavor to address the following key considerations:

- Specify the problem of the study and provide a more detailed elaboration of the research purpose. This is very important when the research problem is multifaceted or complex.

- State the rationale of your research proposal and explain, in an engaging way, why it is worthwhile to conduct.

- Present the core problems or issues that will be addressed. This can be made either in questions or statements.

- Underscore how your research can build upon existing assumptions about the proposed study’s problem.

- Elaborate on the details of your methodology to conduct your study, including the key sources, analytical approach, etc.

- Clearly establish the limits of your proposed study to provide a clear research focus.

- Provide definitions of key terms or concepts, if necessary.

The methodology section is one of the most important sections of your proposal. It demonstrates your understanding of the steps and skills necessary to undertake your intended research. It should be as explicit as possible, detailing how you will collect, analyse and present your data or research.

Make sure to cover the following when describing the methods you will utilize:

- Establish the research process you will engage in, including the method you will use for interpreting the outcomes with regard to the problem of the study.

- Do not simply discuss what you plan to accomplish from using the methods you will select, but also describe how you will use the time while utilizing these techniques.

- Note that the methods section is not merely a collection of activities. Since you have selected the approaches, you should also use it to argue why it is the best approach to examine the study problem. Explain this clearly.

- Finally, foresee and acknowledge any possible obstacles and drawbacks when you undertake your research design and provide a plan of action to solve them.

Examples of methodologies include:

- Quantitative or qualitative research

- Experimental methods in psychological research

- A specialised approach to analysing concepts in philosophical research

Your choice of methodology should be justified by your research questions.

Your choice of methodology should be justified by your research questions. For example if you are examining the relationship between two or more phenomena, a correlational methodology would be appropriate. Alternatively, a case study methodology would be appropriate for researching complex phenomena in their natural setting.

Be sure to describe your intended data collection and analysis techniques with as much detail as possible. They might change as you conduct your research, but you must still demonstrate that you have given a lot of thought into the practicalities of your research at this early stage. You should also note any major questions yet to be decided upon.

If you are gathering a sample of people or documents, you should outline your procedures for choosing this sample.

If you intend on giving interviews or handing out questionnaires, you should provide examples of the types of questions you will ask.

If you intend on using experimental situations to collect data, you should describe as many of its elements as possible. This could include:

- Your chosen subject types (age, school level, quantity)

- Types of materials to be used

- What will be measured (achievement, attitudes, beliefs, etc)

- Data collection methods (self-reporting, observation, clinical diagnosis)

You can use these guide questions when framing the potential ramifications of your proposed research:

- What could the outcomes signify when it comes to disputing the underlying assumptions and theoretical framework that support the research?

- What recommendations for further studies could emerge from the expected study results?

- How will the outcomes affect practitioners in the real-world context of their workplace?

- Will the study results impact forms of interventions, methods, and/or programs?

- How could the outcomes contribute to solving economic, social, or other types of issues?

- Will the outcomes affect policy decisions?

- How will people benefit from your proposed research?

- What specific aspects of life will be changed or enhanced as an outcome of the suggested study?

- How will the research outcomes be implemented and what transformative insights or innovations could emerge when they are implemented?

All university research is expected to conform to acceptable ethical standards and proposals. Research involving human participants must also be approved

Ethical concerns can arise in how research is conducted and the ways these research findings may later be used. You must take into account any areas of responsibility towards your research subjects at the planning stage, and provide strategies for addressing them in the methodology.

Examples of areas of responsibility could include:

- The securing of informed consent

- Confidentiality

- Preservation of anonymity

- Avoidance of deception or adverse effects

A research proposal involving Māori and minority groups/communities should demonstrate that the researcher has had adequate background preparation for working in that area. It should also outline the extent to which members of that group/community will be involved or consulted in the overall supervision of the project and the dissemination of the research findings.

1. Follow the instructions!

Read and conform to all instructions found on the council website. Make sure that your proposal fits the criteria of the competition.

2. Break down your proposal into point form before writing your first draft.

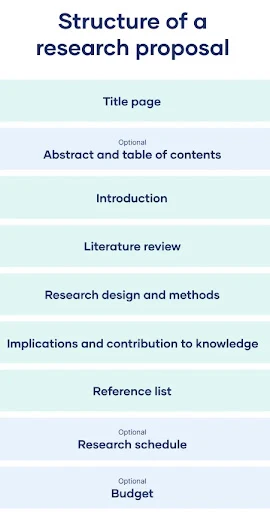

Based on the total length of the proposal, decide whether you will have headings/subheadings and what they will be (e.g., Introduction, Background Material, Methodology, and so on).

These headings can be selected based on the advice given in the specific award instructions. For each section, lay out in point form what you will discuss.

3. Know your audience.

- Describe your research proposal in non-technical terms. Use clear, plain language and avoid jargon.

- Make sure your proposal is free of typographic and grammatical errors.

- Remember that, at every level, adjudication committees are multi-disciplinary and will include researchers in fields other than your own.

- Therefore, follow the KIS principle – Keep It Simple! Reviewers like it that way

4. Make an impact in the first few sentences.

Reviewers are very busy people. You must grab their attention and excite them about your project from the very beginning. Make it easy for them to understand (and thus fund) your proposal.

Show how your research is innovative and valuable. Remember, too, to show your enthusiasm for your project—enthusiasm is contagious!

Organize your proposal so that it is tight, well-integrated, and makes a point, focused on a central question (e.g., “I am looking at this to show...”).

Depending on the discipline, a tight proposal is often best achieved by having a clear hypothesis or research objective and by structuring the research proposal in terms of an important problem to be solved or fascinating question to be answered. Make sure to include the ways in which you intend to approach the solution.

5. Have a clear title.

It is important that the title of your project is understandable to the general public, reflects the goal of the study, and attracts interest.

6. Emphasize multidisciplinary aspects of the proposal, if applicable.

7. Show that your research is feasible.

Demonstrate that you are competent to conduct the research and have chosen the best research or scholarly environment in which to achieve your goals.

8. Clearly indicate how your research or scholarship will make a “contribution to knowledge” or address an important question in your field.

9. Get the proposal reviewed and commented on by others.

Get feedback and edit. Then edit some more. And get more feedback. The more diverse opinion and criticism you receive on your proposal the better suited it will be for a multi-disciplinary audience.

10. Remember that nothing is set in stone.

Your research proposal is not a binding document; it is a proposal. It is well understood by all concerned that the research you end up pursuing may be different from that in your proposal.

Instead of treating your proposal as a final, binding document, think of it as a flexible way to plan an exciting (but feasible) project that you would like to pursue.

To finish your proposal on a strong note, explore the potential implications of your research for your field. Emphasize again what you aim to contribute and why it matters.

For example, your results might have implications for:

- Improving best practices

- Informing policymaking decisions

- Strengthening a theory or model

- Challenging popular or scientific beliefs

- Creating a basis for future research

Ans : Some universities do not require a detailed budgetary allocation for proposed studies that only involve archival research and simple academic research, although some still do. However, if you are applying for research funding, you will likely be instructed to also include a detailed budget that shows how much every major part of the project will cost.

Be sure to verify what type of costs the funding agency or institution will agree to cover, and only include relevant items in your budget. For every item, include:

- The actual cost present how much money do you need to complete the entire study

- Justification discuss why such budget item is necessary to complete the research

- Source explain how the amount was calculated

Conducting a research project is not the same as buying ingredients when cooking meals. So how do you make a budget when most entries do not have a price tag? To prepare a correct budget, think about:

- Materials Will you need access to any software solutions? Does using a technology tool require installation or training costs?

- Time How much will you need to cover the time spent on your research study? Do you need to take an official leave from your regular work?

- Travel costs Will you need to go to particular places to conduct interviews or gather data? How much must you spend on such trips?

- Assistance Will you hire research assistants for your proposed study? What will they do and how much will you pay them? Will you outsource any other activities (statistical analyses, etc.)?

- Abdulai, R.T., & Owusu-Ansah, A. (2014). Essential ingredients of a good research proposal for undergraduate and postgraduate students in the social sciences. Sage Open, July-September, 115. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244014548178

- APA (2014). Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, 6th Edition. American Psychological Association: Washington, DC. Google Books

- APA (2018). Summary Report of Journal Operations, 2017. American Psychologist, 73 (5), 683-84. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000347

- ERC (2019). Rewriting is Rewarding Tips from Repeat Applicants. Brussels: European Research Commission.

- ESOMAR (2019). Global Market Research 2019. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: ESOMAR.

- Gilbert, N. (Ed.). (2006). From Postgraduate to Social Scientist. A Guide to Key Skills. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Google Books

- Glassdoor (2020, August 19). Research Professional Salaries. Mill Valley, CA: Glassdoor.

- Jackowski, M. B., & Leggett, T. (2015). Writing research proposals. Radiologic Technology, 87 (2), 236-238.

- Kivunja, C. (2016). How to write an effective research proposal for higher degree research in higher education: Lessons from practice. International Journal of Higher Education, 5 (2), 163-172. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v5n2p163

- Krathwohl, D.R., & Smith, N.L. (2005). How to Prepare a Dissertation Proposal: Suggestions for Students in Education and the Social and Behavioral Sciences. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press. Google Books

- Lyman, M., & Keyes, C. (2019). Peer-supported writing in graduate research courses: A mixed methods assessment. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 31 (1), 11-20. ERIC No. EJ1206978

- Miner, J.T., & Miner, L.E. (2005). Models of Proposal Planning and Writing (pp. 139). Westport, CT: Praeger. Google Books

- NHMRC (2018). Outcomes of funding rounds. Canberra, Australia: National Health and Medical Research Council.

- NIH (2017). Funding Facts. Bethesda, MD: US National Institutes of Health.

- OECD (2019). Researchers. OECD Data. Paris, France: OECD.

- RPS (2016). Peer Review Guidance: Research Proposals. London: Royal Pharmaceutical Society.

- Sudheesh, K., Duggappa, D. R., & Nethra, S. S. (2016). How to write a research proposal? Indian Journal of Anaesthesia, 60 (9), 631-634. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5049.190617

- van Ekelenburg, H. (2010). The art of writing good research proposals. Science Progress, 93 (4), 429-442. https://doi.org/10.3184/003685010X12798150447676

- Wellcome (2019). Grant funding data 2018 to 2019. London: Wellcome Trust.

Comments

Post a Comment

"Thank you for seeking advice on your career journey! Our team is dedicated to providing personalized guidance on education and success. Please share your specific questions or concerns, and we'll assist you in navigating the path to a fulfilling and successful career."